**This research was first published in the May 14, 2025 edition of the Chatham Star-Tribune newspaper as part of Kyle Griffith’s weekly segment entitled “Heritage Highlights.”

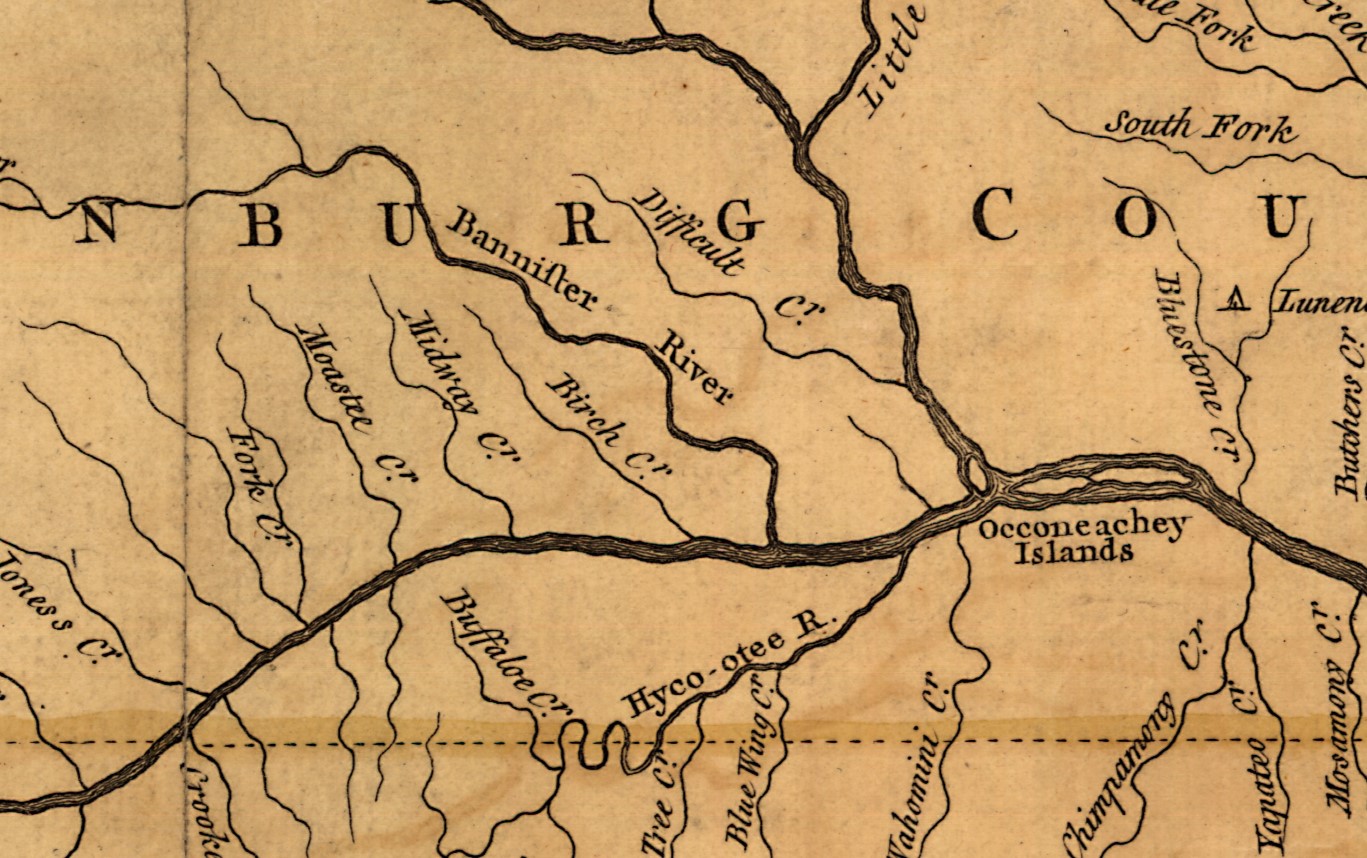

Banister River on a Fry-Jefferson Map from the 1750s

Those who have had the pleasure of exploring an expanse of forest alongside a river as a child may recall feeling fascinated by the variety of plants and wildlife found thereabout. It makes one reflect and wonder how nature has changed since early Virginians lived off the same lands. One can only imagine the scale of ancient trees, miles of dense thickets, and the winding trails once carved into Virginia’s wilderness by woodland bison that have since long vanished from the Piedmont. During the late 1600s, an English naturalist named John Banister documented his findings throughout frontier Virginia, including research into the farming of tobacco. He later became the namesake of Banister River in Pittsylvania County as well as a few people in local history. When John Banister was born around 1650, fewer than five decades had passed since English colonists established the Jamestown settlement in the New World. John attended Oxford University and was sent to Virginia in 1678 as a naturalist and Anglican minister. Throughout following years, he recorded meticulous notes that are partly transcribed here in his original spelling and capitalization.

Banister described the cultivated forms of tobacco in Virginia: “Of our unstable sort of staple commodity, Tobacco, here are two kinds: sweet scented & Aronokoe [Orinoco], differing chiefly in the way of tending or ordering. Sweet scented must be top’d low to about six or eight leaves…by being continually succoured…” Wait until the leaf reaches a “thickness that it will feel like leather.” When ready, farmers “cut them down, let them lye till they are fallen, & then lay them into heaps; When they have to sweat, they bring them into the house [tobacco barn], which is usually built of clapboard about 20 or 25 foot wide; at every 5 foot there goes a range or rail quite cross the house…& there are usually three tire [tier] above, and one below.” He specified that sweet scented tobacco was hung up by the leaf but orinoco was hung “by a peg drove through the stalk.” In terms of curing, “this must be hung thin, else it will sweat away its substance & house-burn. When the middle vein is dry, the tobacco is cured, & will crumble to dust; but in wet weather it gives again…they strip the leaves from the stalks, & make them up in small hands & pack it in hogsheads. Sweet scented tobacco is usually of a nutmeg colour; but Aronokoe, the brighter & nearer a yellow, the better.”

In turn, Banister described the differences of Orinoco tobacco, which “is usually top’t to 14 or 16 leaves…according to the strength of the ground…has nothing near the substance of sweet scented, but is light & chaffy…As soon as ever it is cut down & fallen, wilted so that the leaves will not break in carrying, it must be housed lest it sunburn, & spred abroad upon the floor that it may yellow, not heat or turn dark. We begin to sow our seed in the twelve days, & keep sowing till March, covering the beds with Pine boughs till the weather is over.” He further described which pests to look out for: “…they are subject to be eaten by flies, a sort of sheathwinged insect no bigger than a flea; & in the spring when they are planted out the ground-worm, bud-worm, & after them the horn-worm are great devourers of them. These must be all destroyed…”

He ended the description with a mention of tobacco varieties, which were “known to the Planters by such odd names The Florists give their Tulips; as Townsend, Prior One & All, Anchor, Ffleck, etc.” Banister extensively documented other aspects of animals and Native American culture, but his work was cut short after he was accidentally shot during an expedition with other naturalists in 1692, which the court ruled “death by misadventure.” If he had lived, it’s plausible that he would have become a professor at the College of William of Mary which was established the year following his demise. Banister introduced quite a few new plant species to scientists in England and many of his original drawings still exist thanks to preservation efforts at Oxford University. During the 1720s, surveyor Col. William Byrd II named Banister River in honor of his late friend.