**This research was first published in the August 14, 2024 edition of the Chatham Star-Tribune newspaper as part of Kyle Griffith’s weekly segment entitled “Heritage Highlights.”

Joe Lynch’s Old Blacksmith Shop in Dry Fork

Before the 1950s, rural communities depended heavily on their local blacksmiths and wheelwright shops. The reliability of a smithy’s work directly impacted the productivity of local farms. A good blacksmith was a cornerstone of village life and was respected for their practical handywork.

Blacksmiths were skilled craftsmen and master problem solvers whose engineering minds worked with iron and steel to make and repair almost anything. Using a forge to heat the metal until it was red-hot, they hammered, bent, and twisted it into shape on an anvil. They crafted a wide range of items including nails, hinges, chains, and agricultural implements such as plows, axes, saws, and other blades. They created kitchenware such as pothooks, forks, skillets, and cauldrons. They also crafted horseshoes, bridles, bits, and other tack for work horses and mules. Those who specialized in the shoeing of horses were known as farriers. In addition, blacksmiths made components for wagons and buggies, wherein the partnership of wheelwrights became common. Wagon wheels, axles, and other components were as important as car maintenance is today. The blacksmith forged the metal parts while the wheelwright handled the wooden components.

Blacksmith shops throughout the U.S. were typically situated near village centers, crossroads, and adjacent to other important businesses including general stores or grist mills. The buildings usually featured plain architecture of sturdy frame or stone construction. The front typically had one or two large wagon doors that swung wide open and allowed air circulation throughout the shop. The sweltering room was filled with the roar of the forge, the clanging of hammer on metal, and the hiss of hot iron being quenched in a bucket. The air felt thick with the smells of burning coals.

Becoming a blacksmith typically involved an apprenticeship, where young people learned the trade from an experienced blacksmith. After years of practice, the former apprentice likely opened a new shop or succeeded the position of their mentor.

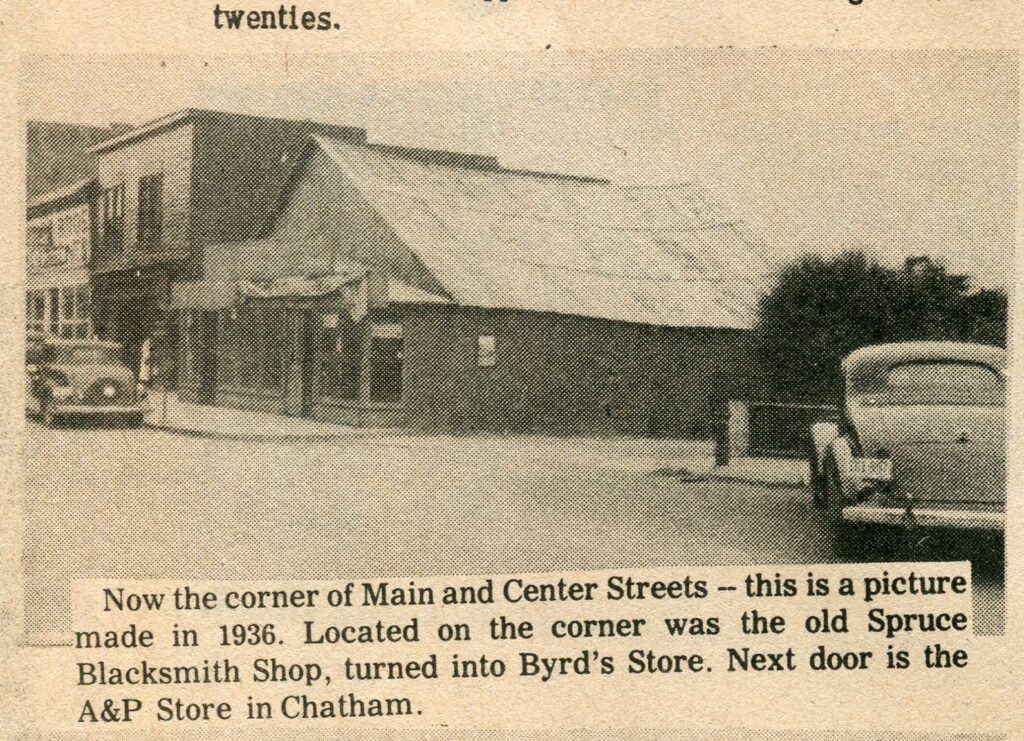

An old clipping from the Star-Tribune showing Spruce’s Blacksmith Shop

A documented by the late historian Pops Osborne, Walton Moore of the Whittles community kept the horses shod at Chatham Hall for upwards of forty years. Dozens of other blacksmith shops operated throughout the county and the 1940 census helps to identify who served among the last of traditional blacksmiths. Lewis F. Riddle ran a garage and blacksmith shop near Chatham. William Henry Winn had a shop in Vance; Ben Haskins at Pigg River, Jacob Cleveland Miller near Pigg River, Edd Arrington in Ringgold, Clarence Wesley Saunders near Banister River, Henry L. Stuart in Callands, and George Coleman Hardy in the Tunstall District.

Wesley C. “Carr” Elliott was both a wheelwright and blacksmith in Dry Fork near Hopewell Methodist Church.

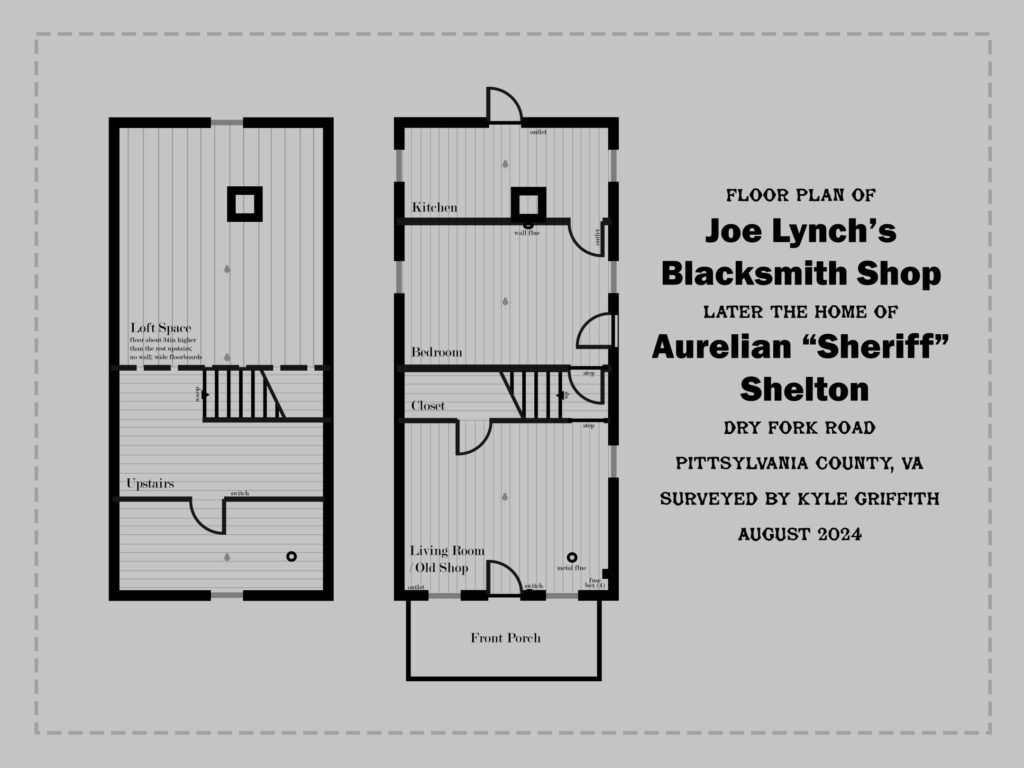

Along the same road, one old blacksmith shop still stands in Dry Fork. In the 1930s, Bennie Yeatts had a new shop constructed and Joseph Ravion “Joe” Lynch (1903-1966) served as the blacksmith until sometime after 1940. Joe’s maternal aunt Alice Pruett Meadows was my great-great grandmother. After the shop closed, it was converted into a house and lived in by Joe’s cousin Aurelian “Sheriff” Shelton (a grandson of Alice). The building is pictured in its current state as of August 2024. Its future is uncertain, but it remains as an important piece of local history and a symbol of village culture.

The craft of blacksmithing is thousands of years old and proved necessary to nearly all cultures across Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Nearly all rural villages had their own blacksmith during the days of the horse and buggy. As the nation progressed and industrialized during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the number of traditional blacksmith shops and wheelwrights steadily declined. The two trades gave way to the science of automotive engines and rubber wheels as gears shifted toward the formation of machine shops and autobody garages.

A floor plan of the old blacksmith shop as of my survey in 2024

Cropped 1980s photograph of the old Joe Lynch Blacksmith Shop courtesy of Vintage Aerial