**This research was first published in the August 7, 2024 edition of the Chatham Star-Tribune newspaper as part of Kyle Griffith’s weekly segment entitled “Heritage Highlights.”

Unmarked fieldstone burial ground in Pittsylvania County containing Johnson, Goard, and Mills family graves.

My x3 great-grandparents and x4 great-grandfather are buried there.

The sprawling forests and overgrowth in Virginia hold many forgotten secrets. A walk through the trees may reveal relics of old foundations, evidence of terraforming, and old family burial grounds. The wild cemeteries may appear as a strewn grouping of long, flat rocks protruding from the earth and nothing more. This was the method of burial for many Virginians throughout the colonial era and into the twentieth century. It makes one wonder about the entire lifetimes of experiences that took place close by.

Family burial grounds were usually established within a short walking distance from the family home, but far enough to keep the areas separate. Rural settlers often selected a location on the property less suitable for farming, perhaps near a rocky treeline. For protection, some burial grounds were surrounded by a dry laid rock wall. In addition, some people planted periwinkle—a hardy groundcover plant—to suppress the weeds and maintain a neat appearance around graves. It usually grows no taller than a few inches, and its waxy evergreen leaves keep year-round.

Periwinkle popping out in a wooded area at an old burial ground

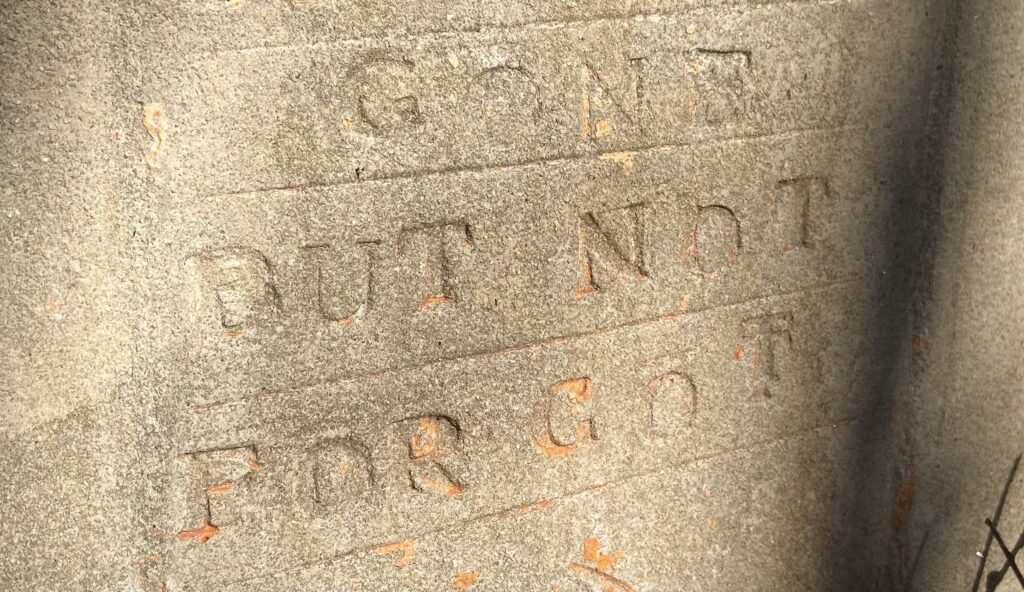

The use of family burial grounds over church graveyards was sometimes a matter of convenience, as some rural families lived miles from their church. Additionally, family cemeteries allowed for the continuation of ancestral traditions, frequent maintenance, and provided a private space for burial on the land in which they likely held strong generational ties. The shift towards public cemeteries began in the mid-19th century, as urbanization increased and public health concerns prompted the development of larger, organized cemeteries. Despite this shift, some families in rural Virginia continued to use unmarked rock markers instead of engraved stones well into the 20th century, keeping a more practical approach to memorialization. The most recent fieldstone marker I have seen was from 1974, with the date written with black paint.

Historically, settlers of the Virginia Piedmont during the 1700s and early 1800s used fieldstones for grave markers rather than more formal engraved tombstones due to practical and economic reasons. Fieldstones, which are naturally occurring stones found on the land, were readily available for families who might not have the financial means to afford ornate engraved gravestones. In contrast to materials like soapstone or granite that have been shaped, fieldstones were left in their natural, unrefined state. Traditionally, both a headstone and a footstone were used to mark the boundaries of a grave, recognizing the extent of the body below. Footstones are typically smaller and simpler than the headstone.

As generations grow and the knowledge of which burials contain whom is not passed down, it may be impossible to know the names of individuals in each plot, or how many burials there are altogether. It is still probable that the main family surnames can be discerned based on property records. For lesser known cemeteries in the middle of the woods, make an effort to document their coordinates, take photos of each stone, draw layouts of the plots, and make sure debris doesn’t fall in and obscure or damage the graves. If the opportunity permits, little stake flags can be helpful to indicate the awareness of the location if overgrowth becomes severe.

The importance of family burial grounds was very evident to me upon a visit to Tangier Island in the Chesapeake Bay. On the island there are about 400 inhabitants across an area less than one square mile, and their families have lived there in some cases over 300 years. The highest point of the island is about three feet above sea level, so burials take place in raised graves, which appear as a headstone with a long slab the length of the casket. Many of the homes have gravestones in the front yards, which are not spacious areas. Perhaps the interred were close relatives, cousins, or strangers to the property owners, but either way the locals maintain the plots and prolong the memorial of those who lived before.

A narrow road on Tangier Island with burials visible in the yard at the right edge and through the fence at the left edge

Family burial grounds serve as a tangible connection to a person’s ancestors and provide a space for reflection. They reinforce a sense of belonging and identity, especially for those who grew up in the same location. However, the preservation of these sites face uncertain challenges such as land development, natural erosion, and vandalism. Through community efforts and a commitment to preservation, burial grounds can be protected from the encroachments of time and disrespectful development. Come together to honor and preserve these sacred spaces, so future generations can continue to connect with their heritage and remember the lives that shaped local history.