**This research was first published in the July 3, 2024 edition of the Chatham Star-Tribune newspaper as part of Kyle Griffith’s weekly segment entitled “Heritage Highlights.”

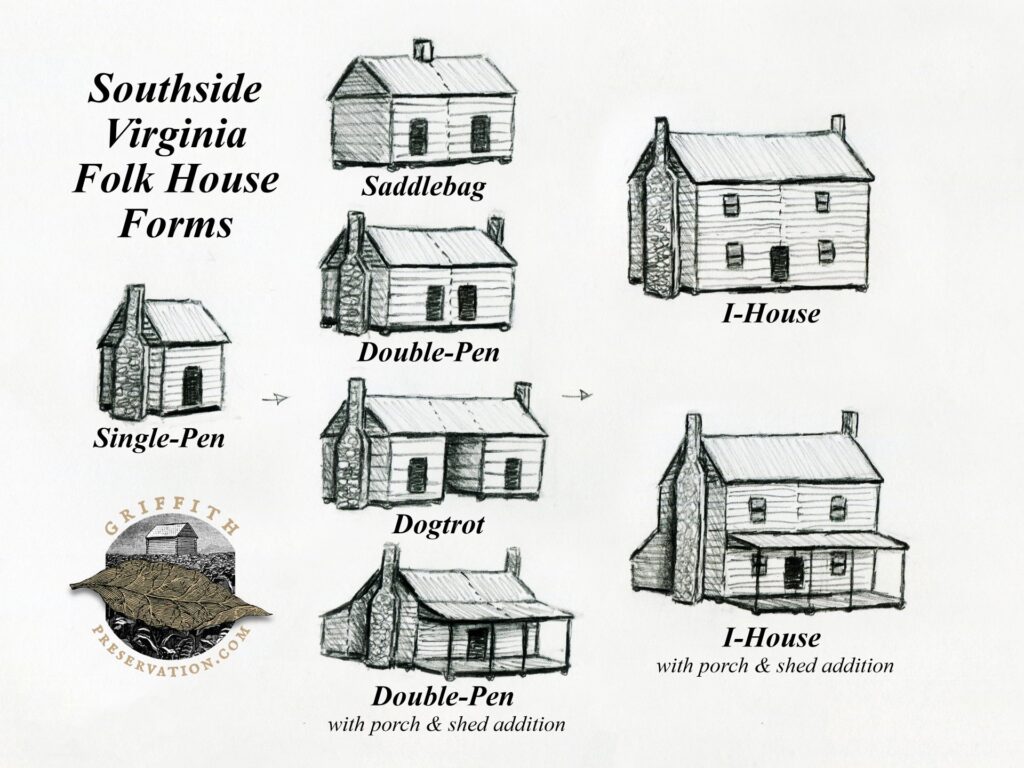

Examples of typical folk houses built during the 1700s and 1800s. Sketches by Kyle Griffith.

Anyone who has traveled through Southside Virginia’s backroads has seen the wide variety of historic architecture the region has to offer. Aside from the imposing brick Georgian mansions and classical Greek architecture, simpler folk houses are not constrained by the rules of high-style architectural movements. Therefore, quaint country homes usually do not fit into specific architectural styles and are referred to as vernacular in style. The elements of folk architecture were determined by the local materials and traditional knowledge available within the region. Early settlers of Southern Virginia developed country homes using techniques passed down from their ancestors.

In the Tidewater region over a hundred fifty years ago, the average rural family lived in simple wood frame homes of hand-sawn planks. In the more mountainous Midland region to the west, log homes became commonplace due to the abundance of old growth timber. Hand-hewn logs were notched and interlocked to create rooms. Sometimes the homes retained the packed clay earth as their flooring. Folk house carpenters used local fieldstone for chimneys and red clay to daub their walls. Settlers of the Piedmont region incorporated elements from both Tidewater and Midland regions into their architecture.

To differentiate vernacular folk houses, one must discern the overall form. Think of each room as one unit, or a “pen.” Among the simplest forms of log or frame homes is a single room with a chimney and a small loft. Keep in mind that old homes, especially vernacular rural structures from over two hundred years ago, have most likely been altered or enlarged over time. Homes grew along with the family. One very common addition was a shed room to the back or the side of a home with a gently sloping shed roof. Often, this room served as the kitchen, or there was a separate kitchen building.

The most prominent form of roofing for southern Virginia houses was a side-gabled roof. This means that from the perspective of the front or back of the house, the roofline is straight across, and the triangular peaks face the sides. At the front of the house, many families opted to build a porch with a gently sloping shed roof. Some porches were later partially enclosed to create an outer storage room.

In order to expand a single-pen home to a double-pen home, folk house carpenters had several choices. Commonly, a room was added to the backside or to the wall opposite the chimney as a mirrored frame extension with another exterior end chimney. Alternatively, if the room was added to the end with the chimney, it could be altered to act as a central chimney for both rooms in a form known as a “saddlebag” house. Sometimes there were two separate entrances. A third option was to build the new room a few feet away from the existing one and connect them with a roofed breezeway, which directed cool air through the passage. Some families used this breezeway as a dining area on hot days. These forms of segmented dwellings are known as “dogtrot” homes. As time progressed, some dogtrot breezeways were enclosed to create a central hall and loft access. Those without a trained eye may never suspect a building to have been separate structures in the past. Together, the combined rooms create a common form known as “hall-and-parlor.”

In terms of vertical expansion, some frame and log homes were improved from a single-story home with a loft to a one-and-a-half-story home with a loft. The sloping walls reduce the amount of usable floor space compared to downstairs. Families with the means to further expand their homes might develop them into a form known as an “I-house.” The I-house typically has four rooms, with a central passage and stairs. It is always a two-story structure, at least two rooms wide, and has a narrow and symmetrical layout.

Understanding the evolution of vernacular architecture in Southern Virginia reveals how early settlers adapted their building techniques to local materials and family needs. From single-pen log cabins to the more expansive I-houses, these are just a few forms of folk houses that were commonplace within Southside Virginia. Old homes tell a story of adaptation and growth, or sometimes they haven’t changed much at all. Thousands of families lived within little shanties and cabins with crooked doors, unpainted walls, and only the essential furniture for cooking and sleeping. These humble yet enduring structures offer a glimpse into the past, reminding us of the resourcefulness and enduring spirit of Virginia’s rural communities.