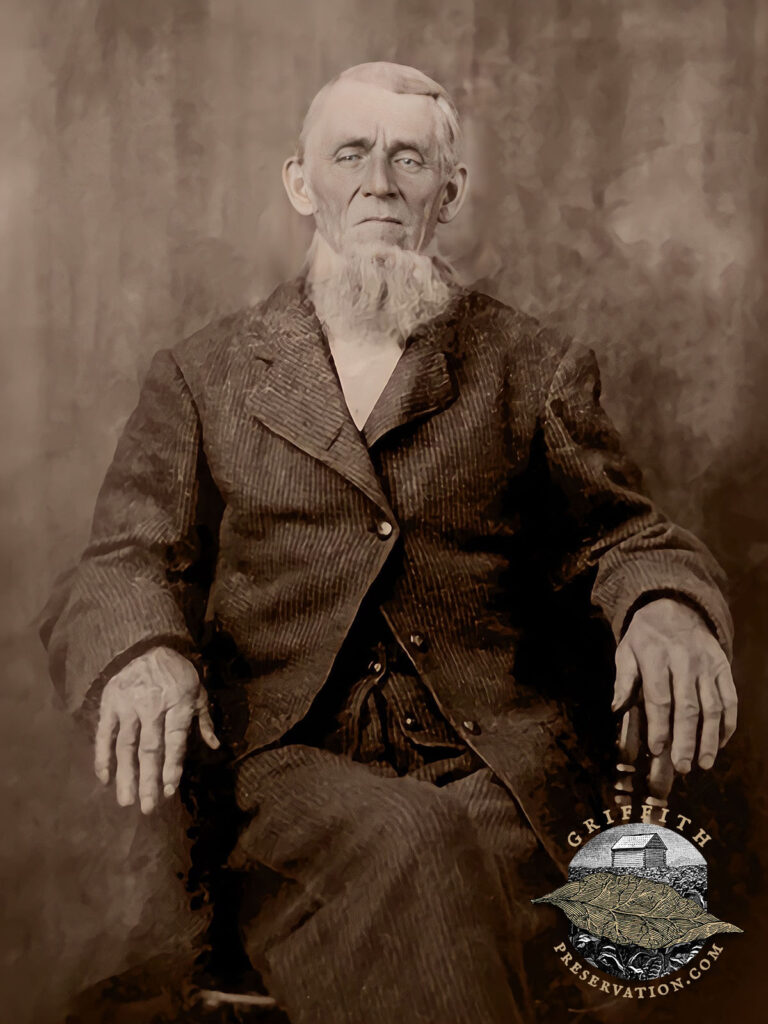

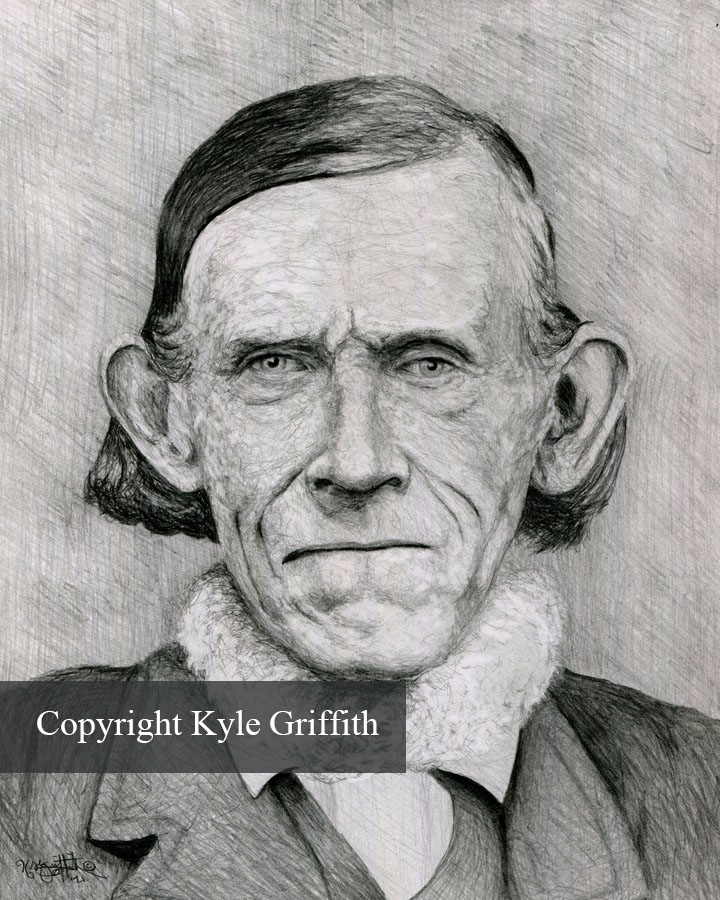

Owen S. Adkins, Sr., circa 1870s

A quiet life in the vast rural hills of a newly independent nation represented a form of freedom. In the decades following Independence, the Virginia Piedmont region saw the rise of a productive generation who established their own legacies on the land. One notable figure, Owen Sanford Adkins Sr. was born in the 1780’s to a large family in the rugged foothills. He had seven other siblings. Through both of his parents, William Adkins and Mary Hardeman, the Virginia roots were several generations deep. His ancestors traveled from England to the Virginia Colony in the seventeenth century. Owen’s grandfather, William Adkins (or “Atkinson”) operated the oldest mill in Pittsylvania County history beginning in the 1740s.

Young Owen became thoroughly familiar with the expanse of Turkey Cock Mountain, his homeland. Part of this range marked the boundary between modern-day Franklin and Henry counties, extending into parts of Pittsylvania county. The terrain was characterized by dense forests, rolling hills, and fertile valleys, providing ample opportunities for hunting and farming. However, the mountainous landscape also presented challenges, such as limited arable land and rugged terrain, which shaped the lives and livelihoods of the inhabitants.

Out of necessity, Owen honed his skills as a hunter, gaining expertise in hunting game such as bear, deer, squirrels, and wild turkeys. To earn a living, he did not farm but instead engaged in various competitions of luck and skill, including foot races, shooting matches, card games, dollar pitching, and wrestling. These endeavors established him as a respected opponent and admired local athlete.

By the age of twenty-four, Owen had married and constructed a small log house about one hundred feet away from his childhood home. Around 1815, he adopted a non-conventional life philosophy and was convinced that he could have as many wives and children as he could properly support. Over a twenty-one year period, his first wife bore nineteen children. Additionally, five years into their marriage, Owen built three houses nearby for three other women with whom raised families in a polygamous relationship. Following the death of his first wife in 1830, he entered into another marriage and continued to raise families beyond this second union. While the precise number of children fathered by Owen remains uncertain, it is generally agreed that records account for at least seventy, though he himself hinted that there might be more than a dozen unaccounted for. During his later years, it was estimated that approximately 550 of his descendants lived within a five-mile radius of his home. His descendants typically had families of six or more, extending through several subsequent generations. Some of his descendants and extended family refer to him as “Owen of All.”

In his nineties, Owen Adkins attracted the attention of a New York-based news journalist interested in his unconventional lifestyle. The writer traveled eagerly by horse and buggy to conduct a lengthy interview with Mr. Adkins, which was first published in the New York Daily Herald on March 7, 1878. The article bore eye-catching titles, referring to Mr. Adkins as “A Modern Patriarch” and “A Mormon Without a Revelation.” Much of this brief biography draws from that source and oral histories. The existence of someone like Owen Adkins in modern-day Virginia may seem improbable, but it reflects the unique circumstances of his era. His generation was the offspring of frontiersmen who possessed the practical skills to sustain their own self-reliant world within their homestead’s view.

While Owen Adkins serves as an exceptional example of life in the past, it underscores how entire communities and villages could emerge from just a few individuals. Before the 20th century, the Piedmont region was predominantly rural, offering limited opportunities to meet people beyond one’s immediate family and community. Some marriages were driven by practicality rather than romantic love. In isolated communities, it was not uncommon for third, second, or even first cousins to marry. However, within a context of limited social and economic mobility, marrying distant cousins was seen as a culturally acceptable and practical solution to the challenges of rural life. In addition to practical considerations, cultural factors played a role in partner selection, with a strong emphasis on preserving bloodlines and family traditions. Nonetheless, cousin marriage carried certain risks, including an increased likelihood of genetic disorders and health issues for future generations, risks that many rural communities at the time did not fully understand or acknowledge.

Throughout his life, Mr. Adkins maintained a strong connection to his roots, living a simple yet fulfilling existence in the mountains of Virginia. His resilience, independence, and unorthodox lifestyle continue to fascinate and inspire those who hear his story, making him a truly unique figure in the history of the Virginia Piedmont region.

Pingback: Adkins Family Origins in Pittsylvania County – Griffith Preservation