**This research was first published in the April 24, 2024 edition of the Chatham Star-Tribune newspaper as part of Kyle Griffith’s weekly segment entitled “Heritage Highlights.“

In the eighteenth century, prior to the Revolution, the James River was not merely a geographical feature but the very backbone of economic survival and prosperity in tobacco farming. The river functioned like a highway, transporting millions of pounds of tobacco through ports along its banks. There the tobacco was inspected, taxed, and continued across the ocean to sell in European markets. Insightful details about this system of trade and other desirable goods were recorded in issues of the Virginia Gazette newspapers from over 250 years ago. Here I have transcribed some of the fascinating statistics available on the variety of imports and exports from Southern Virginia.

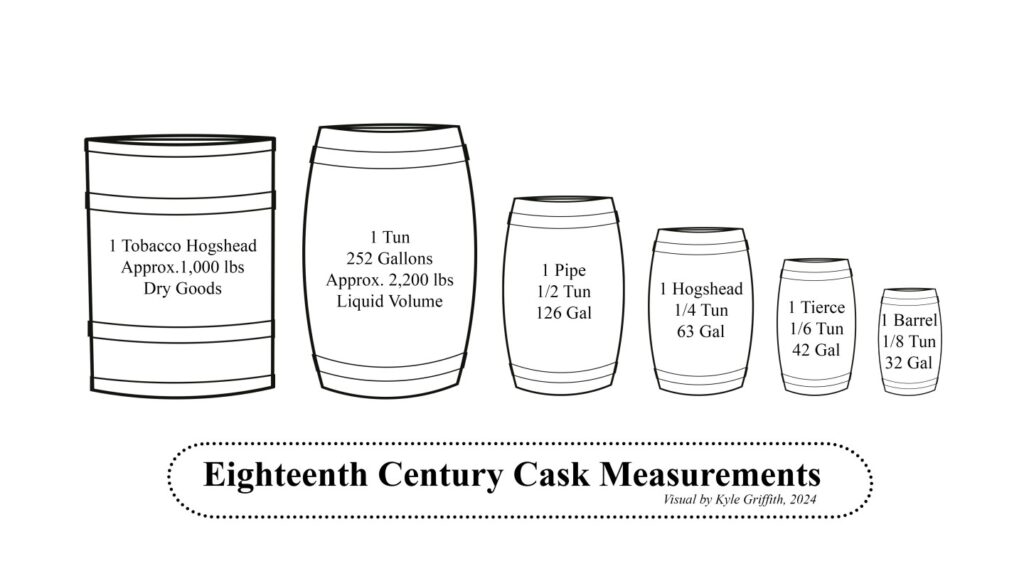

First it is necessary to clarify a few of the old fashioned cask sizes. Cured tobacco was prized into barrels called hogsheads (abbreviated “hhds”) which were typically about 1,000 pounds. The very large and cylindrical hogsheads lacked a typical bulging barrel shape to allow it to transport it along rolling roads like a wheel. However, a hogshead of liquid was different, and typically held about 63 to 64 gallons. See the visual to compare common cask sizes of the eighteenth century.

One very old issue of the Virginia Gazette provided “a list of all ships and vessels, which have cleared out, in the upper district of James River, from the 25th of December, 1745, to the 25th of March following.” Here are three notable examples and their exports (Parks, May 29, 1746, pg. 4): First, a ship called Roberts & Mary, owned by Robert Wilkie, bound for London. The crew exported 277 hogsheads of tobacco and 2500 staves for making more barrels. Second, a ship called London, owned by Jonas Newbam, bound for London. The crew exported 641 hogsheads of tobacco, 3 hogsheads of skins, and 6000 staves; one case, containing a looking-glass, & a bale of “return’d woollens.” Third, a snow (large, two-masted vessel) called Elizabeth, owned by James Heastie, bound for Glasgow. The crew exported 375 hogsheads of tobacco, 6000 staves, one bag of cotton wool, 200 feet of walnut, and 400 feet of oak.

Another newspaper issue from 1768 lists ships that entered the James River. The goods they brought were noticeably different from Virginia exports (Purdie and Dixon, Jan. 14, 1768, pg. 3). First entered a vessel called Fame, owned by William Williams, from Salem, Massachusetts. The crew brought 130 weight of loaf sugar, 20 hogsheads of Anguilla salt, 500 weight of cheese, sundry wooden and earthenware, 2 barrels of pickled fish, 3 barrels of blubber, 15 barrels and 2 hhds. of rum, 5 hhds. of molasses, 4 barrels of sugar, and 200 weight of pot iron. Second, a vessel called Elizabeth, owned by Thomas Coleman, from New York. The crew brought 20 kegs of bread, 12 boxes of candles, 20 barrels of apples, 2 millstones, and 1 hhd. of sugar. Third, a vessel called Defiance, owned by Jeremiah Havens, from Boston, Massachusetts. The crew brought 2 cases of cabinet ware, 20 barrels of New England rum, 2 trunks of women’s shoes and haberdashery, 15 kits of salmon, 2 hhds. of loaf sugar, 1 hhd. of tin ware, 1 bundle of mill saws, 50 iron tea kettles, 2 boxes of brown soap, and 6 half quintals of fish (1 quintal = 100 lbs).

For a final comparison, here are some statistics about total products exported from the upper district of James River between October 1765 and October 1766 (Purdie and Dixon, 2 Feb. 12, 1767, pp. 2-3). Over 19,000 hogsheads of tobacco traveled through the James from farmers of the Piedmont and the Tidewater. In addition, other choice items included 321 “tuns” of iron, 4 tuns of logwood, 3 pipes of wine, 13 hogsheads of rum, 117 tierces of bread, 1,205 barrels of tar, 1,305 barrels of flour, 392 barrels of pork, 780 lock stocks (for weapon manufacturing), over 30,000 bushels of wheat, nearly 80,000 feet of wood planks, over 200,000 shingles for roofing, and over 560,000 staves for barrel making.

It is fascinating to quantify and imagine the trade systems in Virginia over 250 years ago. These goods traveled hundreds of miles through the ocean on wooden ships, facing the unknown and unrelenting forces of nature. These quantities don’t compare to the cargo modern ships may transport, but without machinery and automation, the numbers are astounding.